Archive recounting the actions of a heroic young soldier including a gruesome description of hand-to-hand combat in the most important turning-point battles of World War One

Marne River and the Argonne Forest: 1918. Unbound.

An amazing first-hand account by one soldier of heroism and bloody hand-to-hand fighting at the Marne River and in the Argonne Forest, two battles that turned the course of World War One.

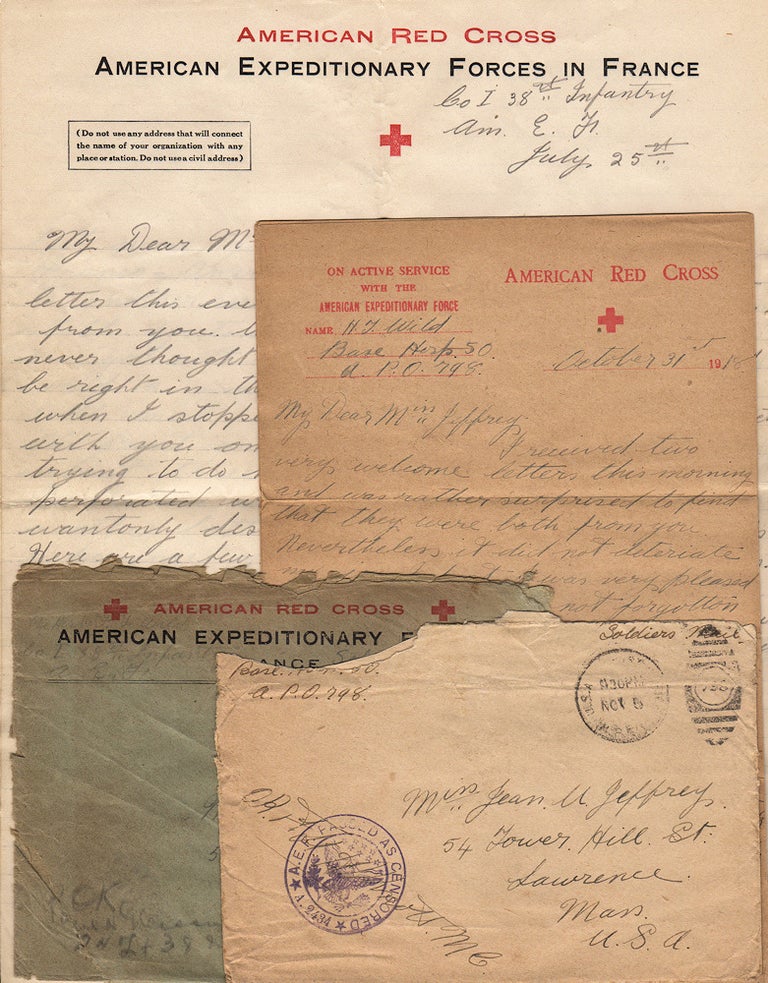

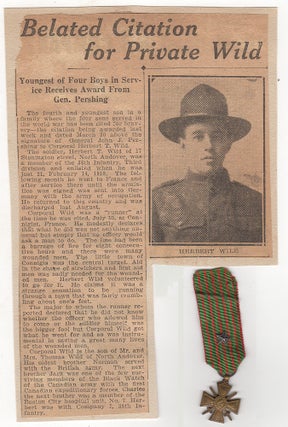

This grouping consists of two combat letters, a French Croix de Guerre, and one newspaper clipping.

The earliest letter, dated July 25, consists of four pages and is enclosed in an envelope postmarked with an indistinct flag cancelation from APO 2 (Paris).

The second letter, written from a Base Hospital and dated 31 October 1918, has seven pages and is enclosed in an envelope, dated November 5, from APO 798 (Meaves-sur-Loire).

The Croix de Guerre has a bronze star affixed to its ribbon.

The newspaper clipping recounts Wild's action at the 2nd Battle of the Marne. Everything is in very nice shape except the envelopes which are worn and have scrapbook paper remnants affixed to the reverse.

Wild enlisted in the Army in February 1918 and was assigned to the 3rd Division's 38th Infantry Regiment. On July 15, 1918, the German army launched a massive assault along the Marne River not far from Chateau-Thierry in an all-out effort to drive through Allied lines and capture Paris. The key crossing point was at the village of Mezy and the only thing that stood in the way was the 3rd Division's 38th Infantry. "On July 15, 1918, the 38th Infantry . . . successfully defended its position on the Paris-Metz railroad, 200 yards from the River Marne, against six German attacks. It was the last great offensive of the German Army and the first fight of the 38th Infantry in World War I. Initially, the Germans succeeded in driving a wedge 4,000 yards deep into the 38th Infantry's front while the U.S. 30th Infantry on its left and the French 125th Division on its right withdrew under heavy pressure. With the situation desperate, the regiment stood and fought. The two flanks of the 38th Infantry moved toward the river, squeezing the German spearhead between them and exposing it to heavy shelling by the 3d Division artillery. The German Army's offensive failed. With this brave stand the 38th Infantry earned its nom de guerre Rock of the Marne. General John J. Pershing declared its stand 'one of the most brilliant pages in our military annals.'" (Stewarts's American Military History, Vol. 2, 2005)

On that day, during eight hours of intensive German bombardment, casualties in the 38th mounted, so with shells bursting around him, Wild volunteered to brave the shrapnel on foot and retrieve additional desperately needed stretchers and first aid supplies from caches in the rear. For this he was personally recognized by General Pershing.

As reported in the accompanying newspaper clipping:

"Corporal Wild was a 'runner' at the time he was cited. . . . The line had been a barrage of fire for eight hours and there were many wounded men. The little town of Connigis was the central target. Aid in the shape of stretchers and first aid men were sadly needed for the wounded men. Herbert Wild volunteered to go for it. He claims it was a strange sensation to be running through a town that was fairly crumbling about one's feet. The major to whom [he] reported declared that he did not know whether the officer who allowed him to come or the soldier himself was the bigger fool but Corporal Wild got what he went for and so was instrumental in saving a great many lives of the wounded men."

And . . . Wild modestly recounts the action in his letter of 25 July:

"I never thought I would get over here and be right in the midst of this terrible war. . . . The night of the fifteenth of July the Germans sent over the heaviest barrage fire ever known on the Western front. We were digging trenches . . . when Fritz opened fire and we crawled down in our trenches on the double. A continual bombardment was kept up for eight hours . . . but we pulled ourselves together and stood the test. . . . The Germans crossed the river Marne on pontoon bridges but were quickly driven back. . . . We were moved on to another sector [where] we drove the Germans back about three kilometers where we held the front line until we were relieved. . . . It was the greatest experience of my life. . . . Our regiment is going to have the Croix de Guerre attached to its colors for the bravery of the troops. We were highly praised by French officials of high ranks, but I am sorry to say that we lost good men in the battle."

Within days of saving Paris, the 38th was again thrust into battle along with other regiments of the 3rd, 28th, and 32nd Divisions. The Americans force-marched to Chateau Thierry in driving rain, many without food or sleep for two days. There at about 0430 on the morning of the 18th, the Americans led the Allied advance behind a rolling artillery barrage. The attack took the Germans by surprise; instead of typical trench warfare, the aggressive attack relied on direct charges, eventually driving the Germans from their positions. By the 22nd, the battle was over, and the will of the German army had been shattered. Although the war would continue for another four months, Chateau Thierry was its turning point. As German Chancellor Georg Hertling later noted, "We expected victory in Paris by the end of July. That was on the 15th. By the 18th we knew all was lost. The history of the world played out in three days."

In his second letter, Wild recounted his part in the battle:

"I have had some terrible experiences since I came over here. No one knows what the boys are going through. . . . We try to do our duty cheerfully even though it is gruesome at times. . . . My duty has been the cause of me killing three Germans that I know of. One I killed with my bayonet and two with a hand grenade. Of course you are shooting at them almost incessantly but we never know if we kill them unless you get near enough to use our bayonets and hand grenades. It is terrible to see the enemy so near that you see the blood lust in each other's eyes. I killed my Germans at Chateau Thierry. We were ordered to take a nest of machine guns that were situated in a shell torn house. I was put in charge of a squad of men and the Lieutenant attacked from one direction and I from another. We advanced . . . with bayonets fixed and in thrusting position. . . . We crept cautiously along the sides of the house and just as we reached the door a German walked right out . . . onto the point of my bayonet before he realized we were there. . . . [I pushed] my rifle forward giving him full benefit of the cold steel at the end of it. His blood poured out and down the stock of my rifle and onto my hand. It seemed to send me mad and just at that moment the Lieutenant gave the order to charge. We went into the house and threw hand grenades into every room, shutting the door before the grenades exploded and opening them after. . . . They did their work well. Too well for the Germans who had their machine guns trained . . . on Americans. . . . Not a German came out of that house alive."

. Very good. Item #008994At the time of listing, nothing anywhere similar to this is for sale in the trade, nor listed in OCLC; neither are there any remotely similar auction records listed at the Rare Book Hub.

Price: $2,250.00